It’s easy to assume that color is color. That the way we see blue, for example, is the same way people saw it 100, 500, or 2,000 years ago.

But that’s not true, says archaeological conservator and museum researcher Sanchita Balachandran. The way we see, experience, and think about color is deeply influenced by our own culture. And if we can transcend the point of view we’re used to, color can become a visceral, sensory window into a world that often feels too far in the past for genuine connections.

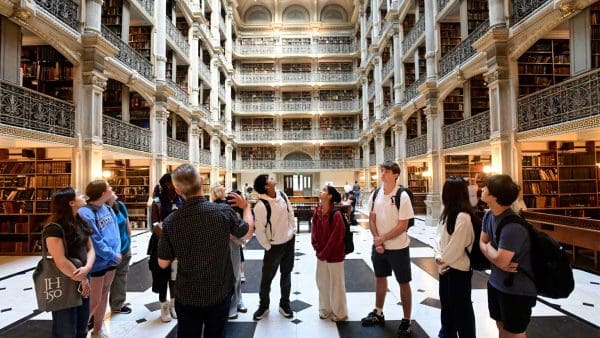

Balachandran, director of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and associate teaching professor, created a course called Ancient Color: The Technologies and Meanings of Color in Antiquity. Through hands-on work with ancient objects from the museum’s Eton Collection, students discover how color was created and used and what it meant. They utilized current imaging techniques along with readings about ancient objects and sites and recent scientific analyses of colorful materials found on them.

“Color is such an integral part of many people’s experience of the world. It is an index by which people make sense of how the world is organized,” Balachandran says. “It’s not just about the visual properties of color, but all of these other sensory experiences and cultural associations that came along with color.”

Reimagine Ancient Statues

The snowy white statues we often see in museums may lead us to believe that their creators worked within a mostly monochrome world. But recently, scholars have pointed out that the objects appear white only because the paints and dyes that once adorned them have worn away or been purposely removed. Modern imaging technology brings researchers a little closer to how the objects were meant to be experienced.

In class, small groups of students bend over painted plaster funerary portraits, analyzing how the surfaces were prepared and what inlaid stones and glass, paints, and coatings the artists might have used. The information offers evidence of artistic intention and choice, which can indicate which workshop produced which piece and help to trace where the materials came from, revealing the trade networks that made them available. By the end of the semester, the students will add their original findings to the museum’s online database.

“It’s just been awesome realizing that no one has done the same type of research on any of these objects,” says Kendra Brewer, a junior majoring in history of art and Spanish.

Brewer’s group studied a female mummy mask from 2nd-century Roman Egypt. Such a funerary mask was a likeness of the person inside the coffin it rested atop, serving as a connection between this world and the realm of the divine; mourners understood the mask to actually be the person, with the ability to communicate with the living. After experimenting with pigments and binders themselves, the students used ultraviolet and infrared light sources to study the characteristics of the mask’s materials, discovering evidence of painted earrings and a life-like skin tone.

Using Science to Consider Art

Such results require interdisciplinary thinking and tapping into knowledge and techniques more common in fields including chemistry and materials science—all part of Balachandran’s goal for the course.

“That’s what I really want the students to see, that staying in your siloed discipline only gets you so far,” Balachandran says. “Students are gathering evidence that no one else has seen since antiquity, but it’s messy—there is a lot of different information to try to make sense of. But that’s the reality of real research, sitting with things that don’t fit together easily and figuring out hypotheses with a team of equally curious people. And the magical part is when that dedicated inquiry brings the ancient world and its people alive again.”