Maryland's longest-tenured United States senator has joined Johns Hopkins University as a professor of public...

Maryland's longest-tenured United States senator has joined Johns Hopkins University as a professor of public...

The Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories has received platinum certification from the LEED program.

John Caron comes to Johns Hopkins from Northeastern University in Boston, where he worked with...

Take a peek into the world of this assistant professor in the Department of the...

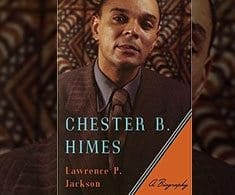

In a new biography, Chester B. Himes, Lawrence Jackson identifies Himes as a key figure...

More stories of note from around the Krieger School.

Hands-on learning in the field of sustainability.

Bishop Douglas Miles '70 reflects on a life dedicated to fighting for social justice in...

Eva Chen, Head of Fashion Partnerships at Instagram

More stories of note from around the Krieger School.

New publications from Krieger School faculty.

We remember Justine Roth, associate professor in the Krieger School’s Department of Chemistry,