he fieldwork of Sminu Bose ’12 took her to India and Cambodia.

he fieldwork of Sminu Bose ’12 took her to India and Cambodia.

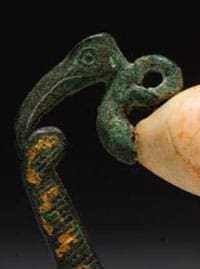

Marie Nicole Coscolluela’s research considers the life of Etruscan children.

Craig Hankin ’76, director of Homewood Art Workshops, talks about why the arts play a...

Sociology Professor Katrina Bell McDonald’s course The African-American Family culminates with the Black Family Saga...

The website for the Science of Learning Institute illustrates its mission to understand the nature...

Professor Benjamin Ginsberg's new book addresses the question, “How come the Jews didn’t resist the...

As managing editor of the Los Angeles Times, Marc Duvoisin ’77 oversees all news departments.

Janine Austin Clayton ’84 was recently appointed director of the Office of Research on Women’s...

In January 2011, Robert Stephen Ford ’80 became the first U.S. ambassador to Syria in...

The Krieger School community mourns the untimely loss of Anne Smedinghoff ’09, a U.S. diplomat...

The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences is something of a Grand Central Station for...

Hopkins’ Archaeological Museum remains dedicated to providing “tangible” inspiration for student research.