When Johns Hopkins University was established at the nation’s first research university, the majority of enrolled students were pursuing doctoral degrees in order to become professors and impart new knowledge to the generations that would follow. Now, nearly 150 years later, doctoral students in the Krieger School find themselves exploring new paths—in addition to academia—and forging innovative ways to share their research with the world.

Powerful forces have come into confluence to reshape the doctoral experience over the past few decades. Yes, the job market within academia has narrowed. The doctoral degree itself has become more versatile, however, as PhDs bring new value to non-academic roles across industry, the arts, and government.

Krieger success stories

Take Patrick Quirk, for example. He received a doctoral degree in political science from the Krieger School in 2014, and is now vice president for global policy and public affairs at UNICEF USA.

“I always saw the value in the ivory tower, as it were,” he says. “But I was more seized with applying research to make sure that it’s relevant to policy in the ‘real world’—and speaking to that audience.”

His Hopkins doctoral degree allowed him to do just that. “To this day, every day—every week at least” Quirk continues, “I apply the training I got at Hopkins in designing research and argumentation and engaging people in the government.”

To this day, every day–every week at least, I apply the training I got at Hopkins in designing research and argumentation and engaging people in the government.”

—Patrick Quirk PhD ’14

Changing landscapes

Such doctoral success stories abound at Hopkins and elsewhere, despite a changing landscape, as today’s PhD students lean into opportunities within academia and beyond.

“More and more PhD students have managed to create pathways into government, nonprofits, and industry,” says Kathrin Kranz, senior director of doctoral and postdoctoral life design at Hopkins. “Employers are also just more aware of the talent that PhD students can add to their workforce and the unique skill sets that they bring.”

The tangible rewards for the Hopkins community are clear. Earning a PhD brings value to the graduates, regardless of which path they follow. And their work teaching undergraduates, or assisting faculty in their explorations, enriches the entire university.

Putting the research first

Research is the foundation of any doctoral journey. The PhD is a goal. A credential. But the skills acquired along the way continue to sustain graduates throughout their career.

Formal requirements (mandatory classes, as well as exams or qualifying papers) vary among departments. But the trend at Hopkins and elsewhere is to streamline candidates’ paths to research,

or to create tight alignments between that activity and degree requirements.

Marc Kamionkowski, the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor in the William H. Miller III Department of Physics and Astronomy, recalls that shortly after his arrival, the department eliminated most required classes and all qualifying exams for its doctoral program. Doctoral students’ new primary task? Get involved in research projects immediately.

“Classes are good,” says Kamionkowski. “But the most important thing, if you want to train a scientist, is how to do science. We’re not here to teach students science. We’re here to teach them how to be scientists.”

…the most important thing, if you want to train a scientist, is how to do science. We’re not here to teach students science. We’re here to teach them how to be scientists.”

Marc Kamionkowski

Learning commitment

Cyril Creque-Sarbinowski completed his doctorate in 2022 with Kamionkowski as his advisor. He says that this commitment to research seeps into doctoral students’ lives as they work toward their degree. “For myself, personally, research doesn’t stop at 5 o’clock,” says Creque-Sarbinowski. “You’re trying to sit down and answer questions at any time you possibly can…. If you want to make meaningful progress and answer deep questions, that requires a lot of time.”

Creque-Sarbinowski has done postdoctoral work at the Flatiron Institute and is doing a year at University of Washington in Seattle, before starting as an assistant professor at Pomona College in fall 2026. He says that the research skills he acquired on his Hopkins journey have been essential to his success. “It’s not something you learn in undergrad necessarily,” he explains. “Active research

is a very different skill. You can do very well in classes, do many calculations, and know how to execute various technical details. But you do not know how to know: What is a good question? How should I execute that?”

Jessica Newby is a PhD candidate in the history department now in her fifth year at Hopkins. Her thesis, “Kinship in Motion: Women and Slavery in 18th-Century Jamaica,” is already attracting attention, including the award of a 2024 Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Innovation Fellowship.

A key figure in Newby’s research is Molia—an enslaved African woman whose story can be tracked through a primary source document from the era known as “The Thomas Thistlewood Papers.” Newby deploys digital and artistic platforms in innovative ways to give Molia’s saga a broader impact and resonance than it might obtain in more traditional venues.

Within and beyond the academy

For instance, an Instagram series titled “Introducing Molia” uses reels to carry the narrative with video and sound. And Newby cites a project called Slavery in Motion as another case in point. It was a collaboration with research colleagues and Black women artists created in the “Remains // An Archive” microlab of the Diaspora Solidarity Lab—a Mellon-funded, Black feminist partnership initiative across multiple universities, including Johns Hopkins.

“We shared this research with [the artists] to create several original pieces that commemorated aspects of Molia’s story through several different mediums, such as painting, watercolor, poems, short film, and music,” Newby explains. A resulting art collection debuted at the Avery Research

Center for African American History and Culture in Charleston, South Carolina, in the fall of 2024, and it was also presented at an event (“Slavery in Motion”) held in January 2025 at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Newby says that the mentoring relationships the BMA event across the finish line. She credits the support of her advisors—associate professors Jessica Marie Johnson and Sasha Turner, and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History Lawrence Jackson—as essential to finding pathways for “a more public-facing and integrative approach” in disseminating her work.

“I’ve been given an opportunity to see a future for my research within academia, but also outside of it,” says Newby. “What it looks like to take history outside of the walls of the academy and find other avenues for it.”

I’ve been given an opportunity to see a future for my research within academia, but also outside of it.”

Jessica Newby

One size doesn’t fit all

A doctoral student’s journey to the degree is highly individual—as is the question of how best to use their PhD as their path opens up afterward.

In forging his career outside academia, Patrick Quirk has worked at the U.S. Department of State and the International Republican Institute and held fellowships at the Atlantic Council and the Brookings Institution. He embarked on his doctorate while holding down a full-time position.

“Before I applied, I took a step back,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Okay, what’s the broad universe of jobs that I could see myself having in the longer term? What type of degrees and training did those folks have?’ And as I looked at those positions, many folks did have a PhD. Sure, it’s about the credential and the access…but just as important is the training that it gives you.”

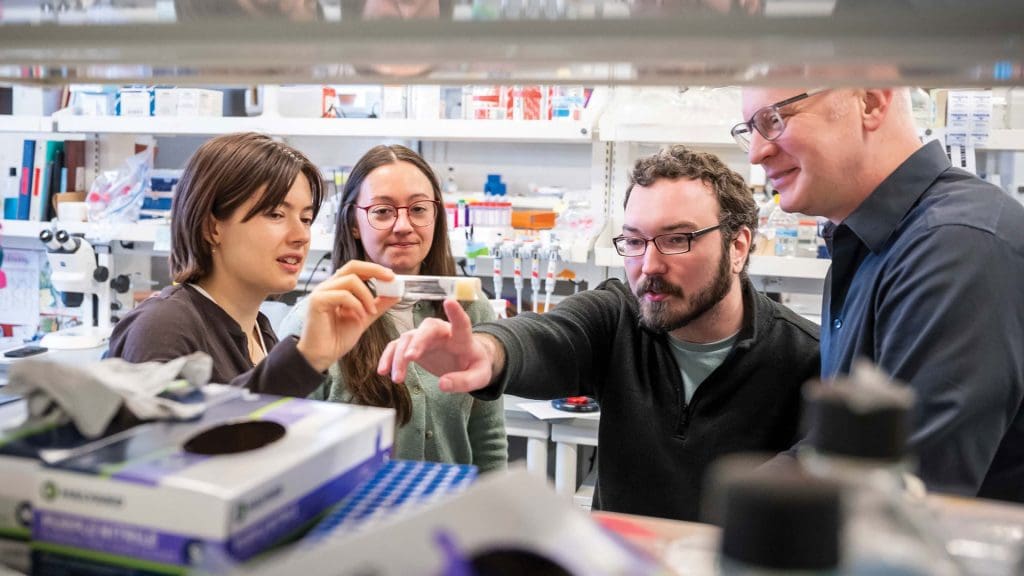

Mentoring plays a vital role

in the doctoral experience.

Professors advise PhD students

and those students, in turn,

are important mentors for

undergraduates. Here, biology

Associate Professor Robert

Johnston ( far right) engages

with PhD students and

Training for flexibility

The questions at the top of Quirk’s mind resonate at the Doctoral Life Design Studio, a professional development office that serves all PhDs and postdocs across Hopkins as part of the university’s broader division of Integrative Learning and Life Design.

The studio boasts a number of established projects that help doctoral students weigh their career options. The Career360 program organizes two-day job-shadowing opportunities, while its flagship Empower Your Pitch program (developed at Hopkins) allows students from a variety of disciplines to distill the essence of their research and find

out how it plays in an annual competition.

When Bridget Purcell, assistant director of doctoral life design, arrived at the Krieger School in January 2025, she embarked upon a listening tour that has led to a number of new initiatives offering specific support to the school’s PhD students (see p. 23).

“We have a renewed emphasis this year, figuring out tailored forms of support to meet a range of needs that spans the humanities and the social sciences and the natural sciences,” she says. “Our approach has been the principle that one size doesn’t fit all, while recognizing that core elements

of the job-seeking process span disciplines.”

Jobs that make a difference

Interest among doctoral students in exploring these questions has increased. “From talking to students, my understanding is that the past year has brought an intensification of the forces already

underway in terms of narrowing academic pathways,” Purcell says.

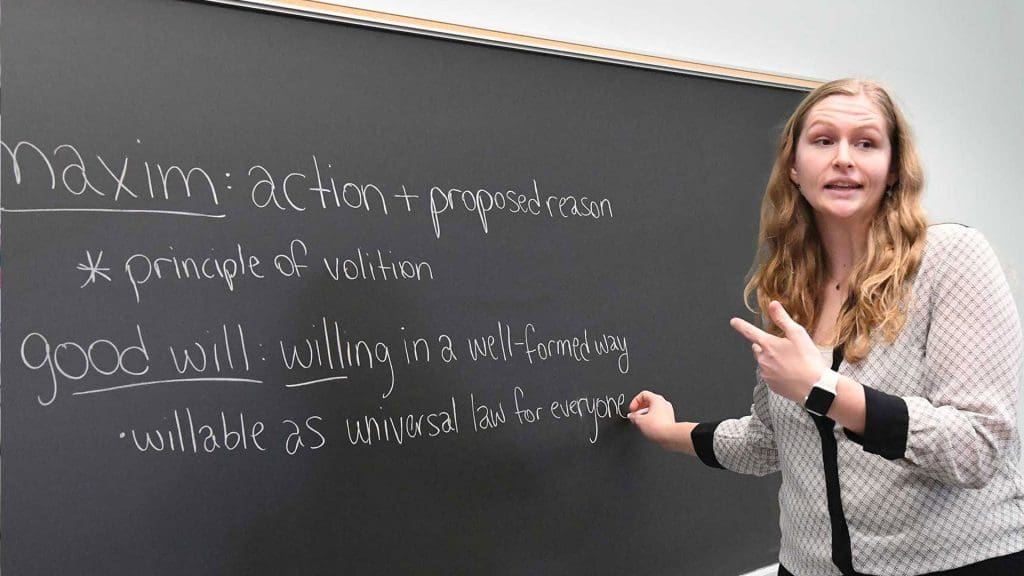

Philosophy doctoral student Emily Scholfield says that she and other philosophy doctoral students were excited to speak with Purcell when she visited their department. “We want jobs that care about philosophy,” Scholfield says. “Jobs that use our writing and communication and teaching

skills, but out in the world where we can see the difference that we’re making.”

Graduate students are a large part of the workforce that makes science move ahead. If you have large-scale simulations, oftentimes it is the grad students running them. A grad student is pushing the project forward.”

Cyril Creque-Sarbinowski PhD ’22

Mary Favret is the Allen Grossman Professor of English, and her Hopkins career has also included a stint as vice dean for graduate education. She points to a recent survey of Hopkins PhD students

since 2008 that captured these shifting trends in post-degree career trajectories.

While a larger percentage of natural sciences PhDs took jobs in private industry, the survey also showed that upwards of 40% of humanities and social sciences doctoral graduates have pursued careers outside of academia. “There’s not one clear pathway,” Favret observes. “It’s kind of amazing the variety of things people have done with their PhDs.”

The survey also revealed other skills embedded in the Hopkins doctoral experience for those who chose a non-academic career, Favret says. “The things that jumped out were related to the dissertation: the ability to do research, synthesize arguments, and acquire highly developed writing and communication skills. Several of them also tied those skills to their teaching [at Hopkins]…. To take a complex idea and present it in a way that other people can readily understand.”

On Your Toes

Perhaps the most important part of any doctoral student’s journey is their relationships with mentors and advisors, who provide a road map for new research and an approach to mentoring.

Newby credits her advisors with ensuring “that my dissertation research began almost as soon as I got to Hopkins.” She says her mentors took “an integrative approach” in every element of her studies, extending the connections between her research and requirements from graduate seminars to field meetings to the core texts for comprehensive exams.

“I didn’t realize that that was what they were doing at the time,” Newby says. “They were actively encouraging me to directly incorporate my personal research interests and my initial ideas of what I

thought I wanted to write about into how I was thinking about the core texts.”

The importance of relationships

Scholfield’s research on connections between the humanities and sciences has made Associate Professor of Philosophy Elanor Taylor a perfect advisor. “She does metaphysics of science and social metaphysics, which are the underpinnings of how we create social structures,” Scholfield explains.

“She also has a background in science communication and ‘trust of science’ in her past career. We work really well together in our mentoring relationship.” She adds that working with William H.

Miller III Associate Professor of Philosophy Monique Wonderly on “moral emotions” such as attachment and trust and personal relationships gives her “a better understanding of trust in the institution of science.”

“I think for me, advising [doctoral] students keeps me on my toes,” says Kamionkowski. “If I was just working at a national lab, and just doing my own research—and not interacting with and advising students—my guess is that I would have had far less breadth and probably been much more narrowly focused.”

Mentoring doctoral students helps Kamionkowski and other physics faculty stay “alert for new things, new ideas” as researchers, he says.

Building the Conversation

Something that often goes unremarked upon is how much doctoral students add to the life of the university as they work toward a PhD.

“Graduate students are a large part of the workforce that makes science move ahead,” says Creque-Sarbinowski. “If you have large-scale simulations, oftentimes it is the grad students running them. A grad student is pushing the project forward.”

Favret says that doctoral students who do opt for an academic career will find the work they do as teaching assistants essential for their future, noting, “It’s a disservice for us to just let them go and hide in their books.”

Balancing research and teaching

The tensions felt by PhD students who must find time for research and other obligations are real. “But if they haven’t done any teaching, all the rest of it can be for naught,” Favret says. “The trick is how to balance [both] and give them an optimal teaching experience that’s real and will contribute

to their training as academics without getting in the way of [degree completion].”

Scholfield sees teaching as an essential part of her activities. “I have my research to do,” she says, “but I love interacting with my students.” As a researcher at “a crux between philosophy and science,” she has a chance to tell undergraduates that “there are ways that you can do both of these things—that philosophy can be really important to what you’re doing. Understanding the ethics behind any choice that you make in your lab is going to be essential to making sure the world goes in the right direction.”

Philosophy doctoral student Emily Scholfield views teaching as an essential exercise in

translating complex ideas for different audiences. Here, she leads a lecture on Immanuel

Kant as part of an undergraduate course.

Newby points to the history department’s Black World seminar—a graduate faculty event held every semester that considers Africans’ and people of African descent’s impact on the making of the modern world, from the slave trade to the present—as a key reason that she decided to pursue a doctorate at the university while still in her master’s program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Becoming a contributor

Engagement in research that pushes into new vistas and multidisciplinary spaces makes Newby a contributor as well as a participant in this vibrant scholarly exchange. “It places me in direct communication and community with other faculty members at Hopkins, both inside and outside of the department…. It’s not just limited to history. And faculty members or graduate students in different areas of study from mine, who have been integral to my development and my growth

as a doctoral student. It also connects you with a broader academic community outside of Johns Hopkins,” she says.

As Kranz, of the Doctoral Life Design Studio, helps Hopkins doctoral candidates navigate challenging currents, she says that the innate strengths that students must possess to earn a degree come into play: “PhD students and postdocs have gone through some really intense periods in their programs. Seeing their resilience is also part of what we’re doing. Reminding them of everything that they’re capable of. Because truly these are outstanding individuals who are able to persevere.”

Targeted Solutions

Doctoral tracks in the arts and sciences at Hopkins are as broad as the Krieger School that houses them. So finding specific ways to help these PhD students forge a career trajectory is a challenge.

Two relatively new programs aim to help newly minted PhDs find a place for their talents and knowledge in a shrinking and uncertain job market.

“Build Your Post-PhD Career Plan in Four Weeks,” piloted with 15 humanities and social sciences PhD students, helped them explore career possibilities by engaging with alumni and other professionals. The balance of the workshop offered a chance to create tailored job documents to

pursue new opportunities.

“Students really felt like it addressed: Where do I begin? How do I get oriented?” says Bridget Purcell, assistant director of doctoral life design for the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. The Doctoral Life Design Studio team is now creating a STEM-facing version for the fall semester, and also adapting it to other divisions.

Career Kit distills essential job market tactics to expand both their practicality and usage into a 30-minute, instruction-based workshop. “Someone can come for that time and get all of the relevant information for a resume, a cover letter, how to network, and how to interview,” says Kathrin Kranz, senior director of doctoral and postdoctoral life design. Doctoral students can opt to stay longer and participatein an interactive session with on-the-spot feedback.